Friday, March 18, 2016

Walt McDougall's This is the Life: Chapter 11 Part 2

This is the Life!

by

Walt McDougall

Chapter Eleven (Part 2) - But No Worse Than The Others

The exterior aspect of great men has always been to me a mystery, gifted as I was, by birth or practice, with the trick of reading at a glance, in most cases, the lines of concealed vanities, conceits, stupidity, kindliness or lust that Time always stencils on the human face. Tom Read, who in spite of his fat seemed stern and even quite fierce, melted to delightful bonhomie in private, Grover Cleveland even when shooting or fishing seemed grumpy, yet a flash of profane humor often lighted his bold features. Once in Newark when a long file of hand-shaking school-teachers had been temporarily halted, he turned to me and gruffly whispered:

"Why in hell can't they send in a few good-lookers?"

Woodrow Wilson's easy affability never seemed genuine to me; he had a sort of swift floorwalker's smirk that was suspicious; a sort of parlor veneer that curled up and dropped off suddenly. Like William Jennings Bryan's attempts at humor, I always regarded Wilson's near-levity as bait.

We had Bryan one night at a free-for-all, catch-as-catch-can contest of wits at the Wilkes-Barre Press Club, where the prodigiously clever Dan Hart, the author of "The Parish Priest," and Frank Ward O'Malley and others as gifted in repartee kept us in roars for two hours while William J. scarcely cracked a smile. In sooth, he seemed rather dazed, and during a walk I took with him afterward he never once referred to the fact that we had witnessed a rather remarkable exhibition of mental gymnastics. I doubt if he really knew it. I have often been with him, but never saw him relax from his prairie frock-coat dignity.

On the other hand, some great men are instinctively kindly and gracious; indeed, all great men are. In the Hotel Bellevue-Stratford, after a banquet one night, a friendly hand helped me on with my overcoat and, turning to thank my helper, I found he was Ambassador Bryce! At the dedication of Grant's Tomb I sat on a rail fence (on Riverside Drive!) beside a coatless perspiring man in black with whom I fell into conversation. He expressed a wish for a drink, and quite wilted when informed that the nearest saloon was at l10th Street. I told him of the booze tent provided for notables back of the Tomb.

"Why! I have an invitation for that!" he exclaimed. "If only my staff were here! I'm Governor Pattison of Pennsylvania."

Whereupon I escorted him to the sacred pavilion, where he found his official staff in full force. You can trust the average Pennsylvania official to find such a place by instinct.

I became acquainted with Sir Thomas Lipton in a similar manner. It was at the great Dewey Parade. Seated together in the grandstand, we fell to talking by his casually noting that we were the only two men in the grand stand wearing soft hats, which led to further remarks, and just as we were beginning to appreciate each other's charms the ex-secretary of the Navy of Cleveland's administration, William McAdoo, approached and informed Sir Thomas that he was seated beside a most dangerous man. Then he introduced me.

But a more notable incident was prefaced by my asking my seatmate on a N.Y. Central train, a distinguished-looking man of advanced years, if he knew anything about Yonkers. When I further inquired as to the best means of reaching Samuel J. Tilden's residence, "Greystone," he assured me that a carriage would be found at the station to take me thither, and then he began to question me. Finally he adroitly drew from me both my name and my purpose in going to Tilden's home, whereupon he informed me that he was Mr. John Bigelow, then writing Tilden's biography, and said that he would take me up to "Greystone" in his carriage.

My object in going to "Greystone" was to make a sketch of the great lawyer. Bigelow very kindly induced him to pose for me and, I suspect, to ask me to dine with them. After dinner, seated in the wonderful library, which is the only thing that has ever caused me to envy another human being, there followed a memorable evening during which there came up for discussion many topics to which, of course, I contributed nothing but two or three frivolous stories, until that of alcoholic beverages was broached. Mr. Tilden was as great an authority on alcoholic matters as he was on books or the law. He rang for his butler and instructed him to bring a certain bottle of Santa Cruz rum which, when decanted, looked like olive oil!

It was, as near as I can remember, some seventy or eighty years old. Rum under any alias had always been to me a detestable drink, but as I almost shudderingly took a sip of this adorably scented ambrosia, I realized what age can do to all things. It was as innocently, seductively soft and delicate as it was innocent-seeming and dynamic. I lapped it lingeringly, prolonging the bliss of about three fingers, perhaps, of the nectar, listening to the Sage of "Greystone" descant upon its virtues at length, a subject plainly very agreeable to him. The draft was finished all too soon. Suddenly I observed his slim wasted form slowly and then more rapidly receding from view into the book-filled background and, turning to Bigelow, saw that he too was removed to an incredible distance. It was like looking through the big end of the telescope.

As I struggled against this manifest delusion, a vast bluish curtain shot with streaks of amber light shut out all vision. Then I felt myself lifted and borne carefully into the upper regions. I recall dimly my shoes being removed. I did not care if they took my appendix away.

Next morning Tilden's valet awoke me, as fresh as a violet. While dressing, I endeavored to extract from him the particulars of this mystic occurrence, but he pretended to know nothing. "At least tell me," I implored, "was anybody else affected as I was?" He grinningly admitted that he had heard that both Mr. Tilden and Mr. Bigelow had retired very early after my knock-out, but his grin made me think that my rum had not been drugged. Long afterward Bigelow said that he believed the normal dose of that brand of Santa Cruz should be about one thimbleful in water, but he would not confess to seeing any optical effects or mirages.

I told the story to Old John Chamberlain, Bill Gilder and Tom Ochiltree, and with tears in his eyes Tom moaned: "My God! Think of being able to have outstayed those two and being left alone with that old bottle! I'd have been pickled for a week!" Chamberlain regarded me with pity and disgust mingled.

"Huh! It's plain you have damn little Scotch blood left in you!" he muttered. "I'd be ashamed to tell such a story on myself!"

He went into old General Longstreet's room and I heard him shouting the tale into the General's ear trumpet. Dear old, grizzly-looking, bearded Longstreet! Crusty without, but all cream and honey within! Once in New York he expressed a desire to obtain a copy of Fox's "Book of Martyrs," having heard of a small-sized edition with all of the old pictures reproduced. I suggested that we walk over to the American News Company in Park Place and see what we could find. We were attended by a languid clerk with a one-way brain who, when I asked for the book, murmured: "I think you'll find it up in that gallery there. All the Fox publications are on those shelves."

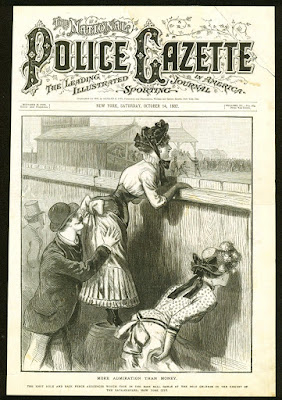

We climbed up to find ourselves facing all the literature ever issued by Richard K. Fox of the Police Gazette! When we got outside I burst into laughter, for which the General demanded an explanation, and as he was very deaf I had to tell the story to all lower New York. That is what always happens when you tell a good one to Thomas A. Edison; consequently he loses many of the very best.

James Gordon Bennett the younger was one of the individuals whose austerity was undisturbed even when behaving most erratically. Sam Chamberlain, who had been his private secretary for a few years, told me that when they were cruising off the coast of Greece, Bennett took him ashore with him to inspect an ancient monastery wherein was a sacred lamp that had been burning more than a thousand years. A monk as old, apparently, as the lamp conducted them to the sacrosanct relic smoking in a niche in the wall. Bennett examined it with great interest and, turning to the monk, asked:

"Do you say that this lamp has been burning for a thousand years? Never been out in all that time?"

"Not in more than a thousand years," asserted the monk proudly.

"Well, it's out now!" snapped the alleged great editor as he blew out the tiny flickering flame.

Sam said he did not know what this characteristic bit of eccentricity cost his boss, but he said that for a time it looked as if both of them were doomed to be cut up by the enraged eremites and fed to the monastery pigs. Bennett finally squared himself with the exalted ruler of the monastery in a private interview during which Sam endured insults in fourteen languages from irate and vermin-infested monks. Sam was always extremely natty and, indeed, immaculate; Bennett was as proud as Lucifer for weeks over this prank.

At the National Convention of 1904, I think, or it might have been earlier, roving about the hotel lobby I came upon a short, cheeky-looking young man dressed very conspicuously and adorned with a beard of carmine hue. This beard alone would have served as a spotlight had its wearer been modest and retiring, but in the forward push of the roseate alfalfa, the impertinent nose and the keen blue eyes, there was revealed consummate assurance, immense egotism and 50-horsepower vanity. I immediately sketched this apparition and then asked his name.

He was Ham Lewis, then an obscure alternate from, I think, Oregon, but he was utterly unknown. It being a dull day, his picture was published and of course attracted attention, and he became one of the Convention sights. It placed him in the limelight temporarily, but that was sufficient for Ham. He kept to the front whenever cameras gathered, and has demonstrated that to get to the top in politics all that is needed is a flossy scarlet beard, a peacock vest and a steady push. Lieutenant-Governor Woodruff devoted much time to reverberating waistcoats, and no one may say it was time lost, but he never reached the height Senator Ham Lewis attained.

Ex-Gov. Bill Sulzer wore a mask of severe dignity that was relaxed only when he was lit up by high spirits, when he became perfectly human. Bill, whom I've known since his boyhood days in Elizabeth, N.J., and who was keenly aware that the least evidence of humor is fatal to a politician, although satire is an invaluable asset, was, in spite of his Henry Clay frown, an exceedingly jovial and generous-souled chieftain with a multitude of friends whom he still retains, and that is more than any other ex-Governor of New York can say. Hughes has a Christmas-tree smile that is as adjustable as an automobile license-tag which to the inexperienced observer closely resembles the real thing, but it is a synthetic product and nothing like the "I-have-swallowed-the-canary" article such as Al Smith and Charley Schwab can deliver.

Richard Mansfield also carried one of those self-feeding smiles that last longest in a photograph. I was preparing a story about actors' make-ups, for which Nat Goodwin and Henry E. Dixey had already posed, and went to Ed Price, Mansfield's manager, to see if I could not add his method to that of the others. Ed thought it a splendid idea and took me to Mansfield's room. When I had explained my purpose he said that it ought to make an attractive article.

"That is what both Goodwin and Dixey thought," I rejoined.

"Are they going to be in it?" he demanded, his smile vanishing just as rabbits vanish as soon as the game laws are up.

"They've both posed for me," said I.

"That lets me out!" he exclaimed. "I can't appear in a newspaper article with any other artist!"

Diffident and reticent as I am by nature, I had to tell him in a few unstudied words what I thought of such egoism, and I am afraid he never thought much of me afterward.

I moved in 1893 to Glen Ridge, then just incorporated, where Edward C. Mitchell, editor of the Sun, was my next-door neighbor. We two gave tone to the tiny burg until a goodly number of taxpayers, golf-players and commuters were gathered. That year, the year of Cleveland's second occupation of the White House, arose the famous "Sugar Scandal." Pulitzer was still inimical to Cleveland, and a World man disturbed his equanimity, but Senator Jim Smith, bless his soul! was a firm friend, as was Senator David B. Hill, who lived at the Normandie, and William McKinley, growing in reputation and influence, was very companionable. He was as genial as was Harding later, but gave the impression of more reserved strength. Harding was the typical jovial Elk whom everybody called "Warren," but I never heard anybody call McKinley "Bill," although many really loved him.

Now Brisbane and I were sent down to bust this devilish Sugar Trust, and in addition de Thulstrup was commissioned to draw a number of portraits of Cabinet officers and other notables. I lived in John Devine's new Shoreham Hotel and loafed a lot at Chamberlain's, where Eddie Somborn, Gene Earle, General Longstreet, Ochiltree, Phil. Thompson, old Senator Teller and other lovers of terrapin and canvasback made their headquarters.

Every bit of Washington gossip, and the city was as permeated with mean and absurd scandal as it is to-day or nearly, collected here as in a cesspool, and had I been a writer I would have been able to dish up some very dreadful-smelling material, but as it was known that I never reported what I heard except funny stories, I heard much. It was on this trip that Brisbane won a large sum, said by him to be six thousand dollars, from four influential Democrats in a poker game and the next day invited me to go with him to purchase a pair of saddle horses. He was so busy riding these animals that he never had time to attack the villainous Sugar Trust at all, and as I could not battle with a trust single-handed, knowing almost nothing about sugar in large gobs as Arthur did, I took Phil. Thompson's word that I was wasting my time, and went off fishing up the Potomac with Amos Cummings and "Terrapin Tom" Murray, who kept the restaurant in the Capitol.

It was my first and only experience of river bass-fishing, which is why it lingers in the memory. Far up the Potomac we journeyed to a foam-footed dam in a wilderness of farms and spent a notable day filled with laughter, wisdom and "fisherman's luck," for we caught nothing, and at eventide we sought a farmhouse to which Amos had been directed by F. Hopkinson Smith, the painter. I scented mint as Cummings asked the aged proprietor if he could put us up for the night and found myself standing in a bed of it beside the door. After supper we talked, with the aged farmer as audience, of many things, sugar, scrapple, strange dishes, travel and fish, and when flying fish happened to be the topic I described their gliding flight as I had seen it in the Caribbean Sea. Suddenly the old farmer burst into wild laughter. "Flying fish!" he chortled. "That's as good a yarn as Hop Smith's about the houses in New York bein' so close together they touch each other!"

Then I went out, cut some mint, and made mint julep to the immense appreciation of our host, who, when our bottle was finished, produced another, demanding that I make mint juleps all night!

Some years afterward I met Tom Murray in New York, where he started a restaurant only to fail, and he asked me if I remembered the ancient farmer on the Potomac. "Well, I went down there a year or two later," he said, "and the old boy had planted thirty-seven acres to nothing but mint!"

During my summer at the Shoreham I used to eat many meals with an estimable and companionable man, E. Barton Hepburn, who was the Republican hold-over Controller of the Currency. I formed the acquaintance of a tall lean Chicago lawyer named James B. Eckels, of my age, who was seeking the position of District Attorney of that section. We talked much together while loafing about the hotel, and became quite chummy. One noon as I sat in the window with Eckels, I signaled to Hepburn that I would join him at lunch just as Jim received a letter by messenger and opened it. He paled and looked rather wildly about, then handed me the letter. It was from President Cleveland, appointing Eckels Controller of the Currency. After congratulating him and partly calming his excitement, I walked over to the waiting Hepburn and told him of this rather queer coincidence, whereupon he asked me to bring Eckels to lunch. Cleveland had taken a fancy to Jim and appointed him on an impulse. He served with distinction, then went into banking in Chicago, and later I heard that he had met with reverses that caused him to end his own life.

Another acquaintance of that period, and one which has always endured, was that with Henry E. Eland, now of the Wall Street Journal, and no longer the rollicking, hilarious boon companion of historians and deep-sea vikings. He was my second in a near-duel that has tainted my reputation for leonine courage for years. I had published some flippant sketches of an old ex-Confederate Major who hung about the Ebbitt House and who, incited, as I have always believed, by Jack Tennant, now editor of the Evening World, promptly challenged me according to the code. As the challenged party I had the choice of weapons, and I chose hatchets. I never heard any more from the Major, but a number of envious reptiles still continue to assert that I was afraid to meet him in mortal combat. It is consoling to me that Eland has always believed in my untarnished honor.

Labels: McDougall's This Is The Life